The Nulhegan River is located in Section 6 of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail , “a 700-mile water trail from Old Forge, New York to Fort Kent, Maine, that … follows traditional travel routes used by Native Americans, settlers, and guides. It is the longest inland water trail in the nation.”

History of the River and the Basin:

In the heart of what is now called the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, the Basin formed when a pool of magma solidified below the earth’s surface more than 300 million years ago and slowly eroded, creating a crater-like “basin” roughly 10 miles across. What once bubbled with hot magma is now one of the coldest lowland areas in the Northeast. Annual snowfall averages 100 inches, and there are typically 100 frost-free days each year. Temperatures range from the low 90s (F) in the summer to -30 degrees (F) in the dead of winter.

The Basin and the area now known as Vermont, New Hampshire, and parts of Maine, Massachusetts, and Canada form the region called N’dakinna, homeland of the Abenaki. The Nulhegan Basin and Nulhegan River were named after the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk, the Abenaki Nation Indians who have occupied what they call N’Dakinna, “our land”, since time immemorial. “Nulhegan” translates in the Abenaki language to “Place of Fish Traps” for the bounty found there.

Note: It appears that the name “Cowasuck” is an anglicized corruption of the band’s name in their own language, “Ko’asek”.

Map of N’dakinna

from native-land.ca

The following paragraphs are excerpted from “People, Land, and History: The Cultural Landscape of the Nulhegan District”, a report prepared for the Vermont Land Trust by Stephen Scharoun, Edward Frank, Robert N. Bartone, and Ellen R. Cowie of the University of Maine at Farmington and published in 2001:

At the time of European contact, a number of autonomous Western Abenaki groups inhabited the upper Connecticut River valley including the Sokokis and Cowasucks (Calloway 1990). The Sokokis inhabited the area of the valley between their villages at Squakheag located in present day Northfield, Massachusetts to settlements at Bellows Falls. North of the Sokokis were the Cowasucks whose major settlement was located at the Oxbow in Newbury. This settlement was situated at a strategic crossroads with the nearby confluence of the Connecticut and the Wells and Ammonoosuc rivers (Calloway1990; Haviland and Power 1994; Thomas 1985)…

The environs of the Nulhegan District offered important hunting and trapping territories for the Cowasucks and likely other indigenous groups, particularly during periods of local and regional warfare.”

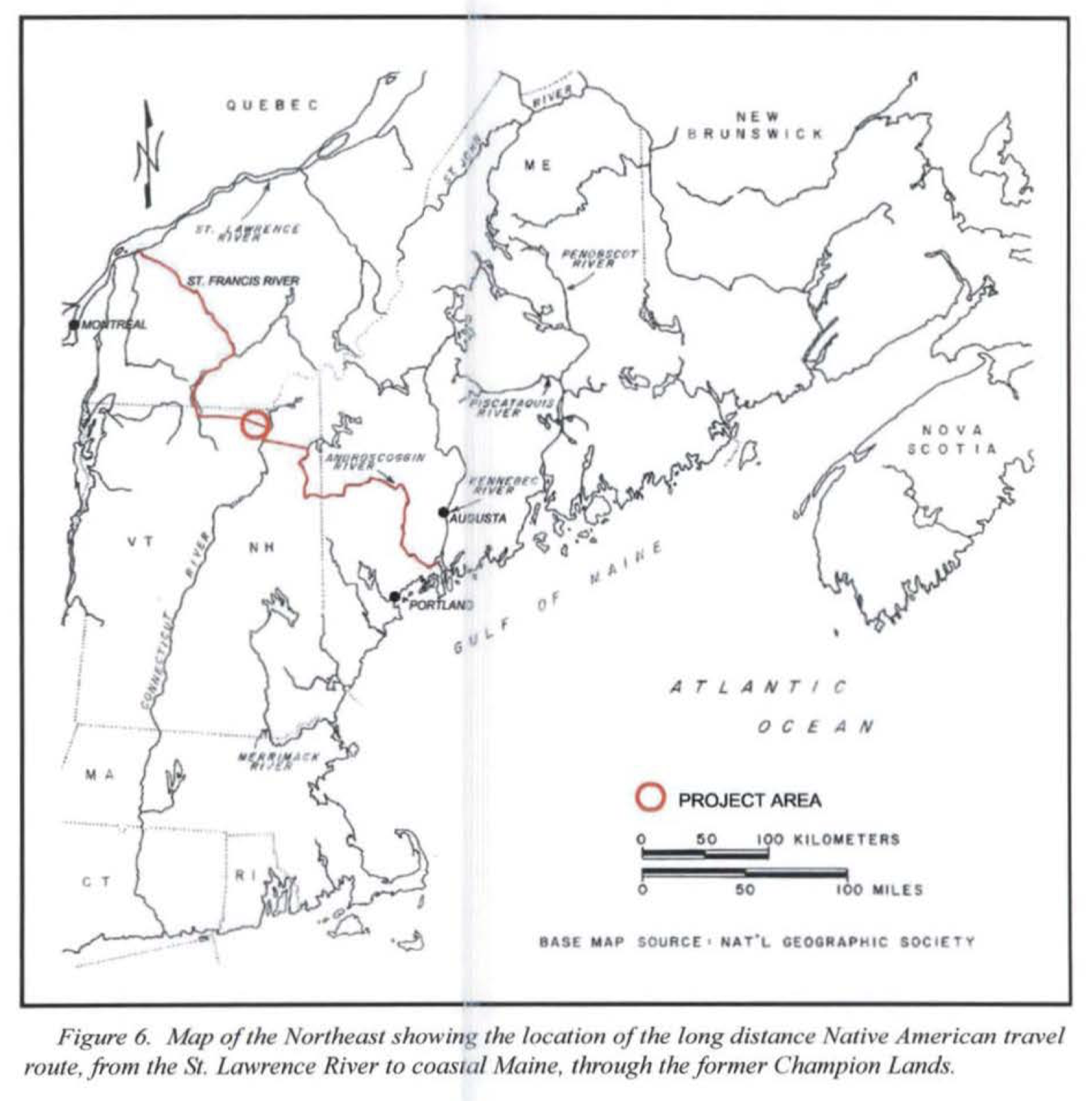

Map from People, Land, and History: The Cultural Landscape of the Nulhegan District

“The Nulhegan River is a segment of a long-distance waterway utilized by Native Americans. This route connected settlements in the St. Lawrence and St. Francis river drainages with locations in the Androscoggin, Kennebec, and Penobscot river drainages, and the coast of Maine. The route was made continuous from the St. Lawrence River, with nominal portage, by navigating the St. Francis and Magog rivers to Lake Memphremagog, whereupon the course followed the Clyde River, which connected a series of lakes and ponds (including Clyde Pond, Lake Sale, Pensioner and Toad ponds) before reaching its source, the outlet of Island Pond. After a short portage to the Nulhegan River, the long-distance route continued on to the Connecticut River. From this point, the prospects of passage through the White Mountains of New Hampshire probably limited the choice to the Upper Ammonoosuc River, whose confluence with the Connecticut River was approximately 22.5 km (14 mi) downstream. According to Hucksoll (1967) and others, this route followed the Upper Ammonoosuc to a point near Milan, New Hampshire, where after a short portage, travelers found themselves in the Androscoggin Watershed.

Native American groups must have frequently traveled through the study [Nulhegan] area on their way to and from the French mission St. Francis (Odanak) on the St. Francis River during the latter portion of the seventeenth century, particularly after King Philips War in 1676. For the next 100 years St. Francis and other missions on the St. Lawrence River provided Abenaki groups throughout northern New England with safe refuge during periods of local and regional warfare (Calloway 1990).”

“A 1756 map (Langdon 1757) shows the Lake Memphremagog-Connecticut River segment of this route and contains the following textual annotation, “This way the Indians frequently came upon the English Settlements - drawn according to information given by Lieut. John Stark, a hunter well acquainted with the woods, who was taken and carried this way to Canada, A. D 1753” (Figure 7). This map confirms that the Nulhegan was also used for militaristic purposes, including the transport of captives to Canada. John Stark was later a guide for Roger’s Rangers. Following their raid on the village of St. Francis in 1759, the Rangers were forced to break up into small foraging bands and to make their way back to forts on the Connecticut River, as best they could. Local records state that several groups used the Nulhegan as their return route. Emmons Stockwell, an early settler of Lancaster, New Hampshire, who survived the ordeal stated that several parties used this route and “crossed the Connecticut at Guildhall and met at Fort Wentworth” (Graviton area) (Blaisdell 1980). A short distance north of Granby, Vermont is a cemetery where two Rangers are buried.”

“Jerome Kelley and Ralph Sweet affirmed that some portions of the Nulhegan River required portage. The historic record notes the presence of a portage trail near where the tracks of the Grand Trunk Railroad skirt along the northern margins of North Notch and French mountains. The possibility remains that an overland path departed from the Nulhegan and passed through the ‘notch’ described earlier, and proceeded along the margins of the Notch Pond and Dennis Pond brooks and on to the Connecticut River, a distance of approximately 8 km (5.5 mi), a route similar to the one used in the early Euroamerican settlement period. “

End of excerpts from “People, Land, and History: The Cultural Landscape of the Nulhegan District”, a report prepared for the Vermont Land Trust by Stephen Scharoun, Edward Frank, Robert N. Bartone, and Ellen R. Cowie of the University of Maine at Farmington and published in 2001:

The following paragraphs are excerpted from the Nulhegan Basin Habitat Management Plan. Note the reference to the Nulhegan Basin Refuge as the “Division”.

“The earliest EuroAmerican presence in the general vicinity of the Division was likely during the mid-17th century 70 miles to the south in Newbury, Vermont. Mission des Loupes (Mission of the Wolves) was a mission established in the Coos region around Newbury, Vermont by the Jesuit priest, Father Sebastian Râle ... The mission was to Christianize Abenaki Indians traveling along the Connecticut River. This is the earliest record of a Catholic Mission in Vermont which attracted Euro Americans to settle in the area. Small, diversified crop and livestock farms, accompanied by water powered grist and sawmills, together with other small-scale industries represent the agents of landscape change during this period.

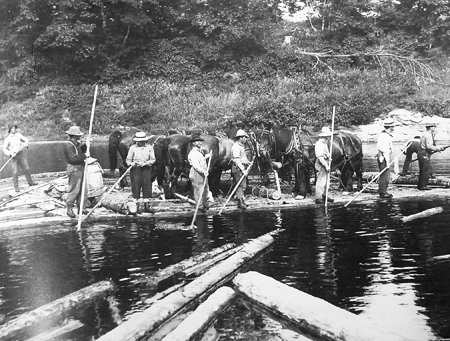

By the 1850’s, a landscape dominated by logging and lumbering began to emerge. This period saw the introduction of the railroad and a simultaneous rise in local wood-manufacturing mills, with extensive holdings in timberland, agricultural fields, housing, and the mercantile trade. By the turn of the century, wood manufacturing and sawmills had given way almost completely to large-scale timber harvesting and associated river drives. The scale of production reached its zenith with George Van Dyke and the Connecticut Valley Lumber Company (CVL). CVL controlled nearly the entire upper drainage of the Connecticut River, including the current Division lands.”

Log Drive on the Connecticut River

Photo Credit: VT Historical Society

“Wood was New England’s first crop. Clapboards were included in the first boat-load of goods shipped from Plymouth to the Old World in 1622 (B. M. Forman, 1970).

The commercial importance and particularly the magnitude of these early wood-related trades, however, should not be overemphasized. Sawmills were typically small-scale, family affairs oriented to local markets. Even the much publicized mast trade barely dented New England’s forests of white pine. Joseph Malone (Malone, 1964), for instance, has shown that at the most only 4,500 masts were shipped to the Royal Navy from 1694 to 1775. Large-scale commercial exploitation of North America’s–and the Division’s–forests awaited the second half of the 19th century (Williams, 1992).

Settlement had engulfed most of the Northeast by the mid-1800s, and included widespread clearing of forests for agricultural expansion. The Northeast, however, still possessed a number of sparsely populated areas which were marginal from an agricultural standpoint. The climate and the remoteness of the Nulhegan Basin limited the realization of a strong, agriculturally based economy.

Log Drive on the Connecticut River

Photo Courtesy of The Island Pond Historical Society

Men and Horses Moving Logs on the River

Photo Courtesy of Island Pond Historical Society

“In the early days of lumbering in the Division, only the larger white pine and red spruce were cut from the woods. With the rise of pulp operations, the smaller red spruce were cut – spruce being favored for its longer wood fiber, which made for strong paper. Later balsam fir and, in many areas, hardwoods were added to the list of pulp species. “

Rolling Logs Off Gravel Bar on the Connecticut River

Photo Courtesy of The Island Pond Historical Society

“Hardwood harvesting began in earnest in 1920 to 1927 with the formation of the New Hampshire Stave & Heading Company (NHSHC). The primary aim of the NHSHC was the harvest of maple boltwood and manufacture of staves and headings for barrels destined for the West Indies sugar trade (Gove, 2003). A railroad was built to the east of the Division lands along the East Branch of the Nulhegan to allow transport of logs to a mill in North Stratford, New Hampshire.”

Train Pulling Load of Logs

Photo Courtesy of The Island Pond Historical Society

Loggers in the Camp on the Sugar Barrel Railroad on the East Branch of the Nulhegan

Photo Courtesy of The Island Pond Historical Society

Hauling the Winter’s Harvest on Runners

Photo Courtesy of The Island Pond Historical Society

“Cutting practices largely followed the dictates of the pulpwood industry; as smaller diameters became more profitable, more extensive and thorough cutting became the norm. The development of mechanized harvesting systems, i.e., skidders and feller bunchers - and lower product requirements in more recent decades encouraged a shift toward even-aged silvicultural management. Clearcutting, or at least cutting all the softwoods to a minimum diameter limit, became the prevailing form of management of the spruce-fir on the Division. This was particularly true during a well-documented spruce-budworm outbreak on the Division [from] the late 1970s into the early 1980s. This often resulted in salvaging of balsam-fir dominated stands with little regard for advance regeneration.

The most recent owner of Division lands– Champion International–regenerated many hardwood stands as late as the mid-1990s. Champion’s management also followed yellow birch markets and others, leading to widespread irregular harvesting within hardwood and mixed wood stands.”

End of excerpts from the Nulhegan Basin Habitat Management Plan

In 1998, Champion International Corporation (a large paper and wood products producer) announced it would sell 132,000 acres of land in northern Vermont, including the Nulhegan Basin. A group of conservation partners, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the State of Vermont Agency of Natural Resources, private investors, the Vermont Land Trust, and The Conservation Fund sought its protection. The Nulhegan Basin Division of the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge was established in 1999 with the purchase of 26,000 acres within the basin. The Vermont Agency of Natural Resources purchased 22,000 acres adjacent to the division to form the West Mountain Wildlife Management Area, and a private timber company (now Weyerhaeuser) purchased the remaining 84,000 acres that surrounds the federal and state properties. The combination of ownerships, with varying yet complementary mandates, provides long-term conservation of important wildlife habitat as well as the preservation of traditional uses of the land.